In this blog post, Gayathri S Nair, junior architect and Ans Maria Sunny, intern at Elemental put together the learnings from our trip to the Mudhouse at Marayoor.

“Work hard. Play hard.” is a philosophy we believe in, at Elemental, wholeheartedly.

To take a break from our hectic work-from-home schedules, this time around, our team thought it’d be fun to go someplace offbeat. A destination unpolluted by humans- a place to unwind and reconnect. Our search for this ended at The Mudhouse, Marayoor.

The Mudhouse is everything unconventional- be it the traditional huts and cottages or the organic landscapes- the care they’ve taken to make it all blend, shows in every corner of the property. And it goes without saying that we had a terrific time in the hills.

During our visit, we realized that the mudhouse is a fine example of sustainable architecture in its most traditional form. Traditional workmanship like this is a treasure that often goes undocumented. The lovely hosts, Shehza and Aman were kind to answer our questions about the property, its construction and maintenance practices.

Elemental: How did the Mudhouse come to be? What is the story and concept behind this initiative?

Aman: The Mudhouse is a family property in which a lot of people are involved. We primarily keep in touch with Mr. Ajit Narayanan and Ms. Roopa Suresh. All of their extended family is equally involved in the activities related to Mudhouse. Mummy (Roopa’s mother), is the most energetic person here and she makes sure not a second goes by, where she’s sitting idly. Her husband Mr. Suresh is also highly supportive of these ideas.

Mr. Dinesh, Mummy’s brother deserves special mention here. It is because of his love for nature and birds that this entire project came into being. Deepak chettan (Roopa’s brother), an ardent nature lover, was the most supportive of a sustainable initiative such as this and he was one of the first people to stay here and help convert this dense forest into a more habitable space without disrupting its natural balance. Their desire to build an authentic mud house in Munnar gave rise to the ‘Mudhouse’ as we know it now. Initially, a single mud house was built for the family, for when they vacationed in Munnar.

However, the cost of maintaining a mud house was far greater in comparison to any other contemporary building, and to meet these costs, the property was listed on an accommodation-letting website. The appreciation we received was overwhelming; mostly from international tourists and to put it short, this was probably the single most compelling reason behind building more mud houses and opening this project to the public as “The Mudhouse”, Marayoor.

Elemental: Could you tell us more about the local skilled labourers who build these mud houses?

Aman: You’ll find that the natives here live exclusively in mud houses as is the norm in the Anjunaadu (a union of five villages of which Marayur is a part) and several other neighbouring villages. Still, albeit to a lesser extent, some of the locals are living in mudhouses. The construction of these mud houses is relatively simple. Although labour and maintenance intensive, the materials are readily available and the skill is known to them.

There are a few downsides to this practice- the thatch needs constant adjusting, the floors need to be glazed with cow dung paste every fortnight in the least and the walls need to be treated similarly at least once every six months. Because of this, a large number of people are voluntarily choosing to shift to concrete houses and a decline in the number of mud houses is observed. This, as result, has led to the process being alien to the younger generation who aren't used to building with natural materials.

Elemental: Do the labourers take up work from different parts of the state or are most works done locally?

Aman: No, they don’t have a need to travel for work. The majority of these people own land here and they have their cultivations. It is when they don’t have much going on in the farms, that they take up mud house constructions or work on its maintenance.

Farming is quite profitable here and they have multiple side hustles. A sense of community is quite prevalent here and this reflects in their day-to-day work as well as their lives. A wedding in the village would mean that the entire community takes time off to celebrate. Most people do not work for a week after there’s been a death in the village.

Elemental: Talking about materials, can all sorts of mud be used for construction?

Aman: I believe most kinds of mud should be suitable for construction. Long before we had concrete, most buildings around the World were constructed using natural materials such as mud, lime and stone. The most widely used was mud. There are several examples of mud architecture that will shock you, like the Great Wall of China, the village of Aït Benhaddou in Morocco, and several others.

However, sandy soil may not be suitable as the clay content in it is extremely minuscule. In several regions, a mixture of mud and lime is also used in construction.

Elemental: What parts of a mud house need regular maintenance?

Aman: The thatched roof, floors, and walls in a mud house need lots of maintenance, the floor being the one that needs the most care. The frequency of this is completely determined by the use of the space. Since ours is a commercial property, we need to keep it in shape. Even though we advise against the use of shoes, slippers, and heels within the mud houses considering their soft floors, our mudhouses require regular maintenance.

We do complete cottage maintenance once a month but this is not how it is done in the local village mud houses. Traditionally, the inhabitants who were mostly farmers would glaze the floors and courtyards with a cow dung paste on days that they weren’t working in the fields. Today, with the increasing number of items at home, people find it tedious to do so without moving out of the house to do the glazing works. Here, at the mudhouse, Devu chechi (house help), glazes the kitchen and dining floors every Friday without fail. She believes that the kitchen isn’t clean and sanitary until she personally does this. Even when she caught the virus, there was no stopping her from cleaning.

At the Mudhouse, below the thatched roof, a non-water absorbing sheet is placed to prevent any discomfort to the guests. This is not the traditional way of laying thatch and so the maintenance we require is slightly lesser than what an actual mud house thatch may. In a traditional thatched roof cottage, the inside of the rooms is smoked with a special concoction and the smoke that rises up creates a non-percolating film under the thatch which reduces any chance of leakage. During maintenance, only the top layer of the thatch is removed and changed.

In the village, the changing of thatch at a house is almost like a festival, with everyone participating to help them complete the work before evening. No work is to take more than a day and what begins one morning, should be over by the evening, regardless of how big the structure is. Most civilizations worked this way, with people helping one another build houses and maintain them. It is very recently that these activities were turned into professions. Traditionally, the Aasharis in Kerala was only involved in the construction of palaces, manas and temples. The homes of the common people were built by themselves.

Elemental: Are the insulating properties of mud very evident when you stay in mud houses?

Aman: Definitely. Earlier, we used to live in a mud house here and in the Summers it’d be cool and in the Winters it’d be warm. Recently, we shifted to a brick house while our cottage was undergoing maintenance works and it had been unbelievably cold in there.

The government has been building homes here under the ‘One-Lakh Housing scheme’ and the people who had shifted to these concrete buildings are having a tough time now. Earlier, they were protected from the temperature drops in their mud houses and now it gets really cold for them for a good part of the year and when the summer begins, the heat is unbearable in Marayoor. The tiled and concrete floors are also not helping. It's comfortable to walk on mud floors barefoot even in the chilly weather.

Elemental: What are the labour charges around here?

Aman: For glazing the floors, female workers charge Rs.500/- per day and for slightly more skilled work, male workers charge around Rs.800/- per day. For any particular construction requirement, you may have, you need to be present on-site all day. Electrical, carpentry, plumbing, and sanitation works all charge around Rs.900/- to Rs.1000/- per day.

Elemental: Have the people here passed on these construction techniques successfully to their future generations?

Aman: Not really. They aren’t interested in letting their children follow this line of work. Everyone wants their children to get better jobs and have better living conditions and opportunities than they had. Companies like Tata and Eastern provide opportunities to the children of their labourers to get white-collar jobs in their company, provided they have achieved a minimum academic requirement the company sets.

The ones that are interested in the next generation having knowledge in and appreciating this practice are worried that their children do not appreciate it.

Elemental: How can we maintain the authenticity of these building traditions?

Aman: It is not as simple as it looks. These structures need a lot of patience, work and care. The desire to maintain an authentic practice won’t last when contemporary structures can be built and maintained at half the cost and for half the work.

For example, the ‘Ermadam’ (treehouse) at The Mudhouse is an authentic construction. However, we estimate it to last without major maintenance work for five years while a similar treehouse replica made of steel sections and adequate reinforcement will last much longer. In such situations, people tend not to go for such structures that need constant work.

In this regard, Ajit and Roopa are and the rest of the team are passionate and value the concept. They’re willing to put in the work and the money to provide authentic experiences to the guests.

Elemental: Are there any particular anecdotes regarding the construction of mud houses that you’d like to share?

Aman: The people here have very strong beliefs associated with the work they do. They only cut the grass and trees necessary for thatch work and construction with relation to the solstices. They believe that the materials will last long only if they follow the system and they’re yet to be proved wrong. We can see an extension of these practices in our cities too, where poojas and other ceremonies are conducted before construction begins, to find suitable dates.

Another example is the treehouse on the property. What would’ve normally taken around a month or two or maybe three to be completed took around a year and a half because of the contrasting schedules of the labourers. Like we mentioned earlier, the sense of community among the people here is very strong. In the event of a death in the village, nobody goes to work and weddings here last a whole week.

Elemental: How do you feel about a sustainable way of living?

Aman: Nowadays, you can see that the sustainable way of life is picking up pace among people in our generation. It is gaining a lot of support and for all the right reasons. If the generations before us had been a little more aware and conscious of their actions maybe we wouldn’t have had to make such drastic changes on such short notice. The media has also been instrumental in spreading these ideas.

I recently happened to see a travel destination advertising itself as sustainable when its A-frame was custom built and brought in from Madhya Pradesh for this purpose alone. So, a lot of things that claim to be sustainable are not in fact so. Young travelers like us need to make conscious efforts to promote awareness of what is sustainable and what is not. A camp within the jungle that blasts music and hosts campfires at night is not eco-friendly. Anything that disrupts the natural balance of things is not sustainable, to me. The previous generation frequenting such places can be excused because they may not understand the relevance of what we say. But when a younger person makes the same mistakes, it cannot be looked past.

So when you do travel, taking the effort to support actual sustainable properties makes a lot of difference- to you and the planet.

Elemental: How would you describe your experience living here for almost a year now? Also, what brought you here in the first place?

Shehza: We got married in 2019 and honeymooned in a remote Himalayan village for two months. After we came back to Kerala, the lockdown began and we were stuck at home. So when the restrictions slowly lifted, we knew we wanted to go somewhere for a month or two and that’s how we found the Mudhouse on Airbnb.

That’s when Aman called Amit and for several reasons, we just couldn’t find a date suitable for both parties. During this time, Aman and Amit hit it off and they regularly began talking. So when we thought of renting a house in the hill ranges for a while, Amit was the first to suggest that we stay at one of their mud houses and do whatever little we can for the betterment of the property. That’s when I took over the marketing and social media departments while Aman focused on landscape and architectural works.

Life is a lot more fulfilling here than in the city. We’re loving the vibes of the place, the simplicity of the people, the pure air and water, and the ease of living here. We’re also planning to expand the Mudhouse shortly.

To know more about the construction details of the mud houses, we conducted an impromptu case study at the property. Provided below are a few details that we found intriguing:

Wall cross-section:

In the cross-section, wooden frames running along the length of the wall are visible. These frames are nailed to the wood members in the walls to give them additional strength and rigidity. Mud work is done once the frame is completed. Plasterwork is done over this. In areas where the plastering is left incomplete, the frames can be visible.

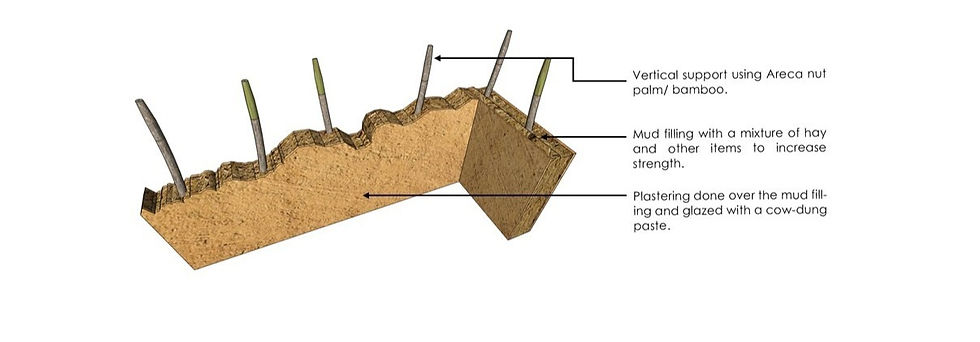

Wall isometric-1:

Initially, frames are placed around where the mud walls should be and earth is filled into the wooden structure. In some instances, 1/3rd of the structure is completed and left to dry, and the next layer is done over it. In the last stage, plastering is done over the wall with a cow dung paste.

Corner junction detail:

Cross-sectional view of two mud walls joined at the corner of a room, and an Areca nut tree placed as reinforcement in the corner. Like a lattice, it is both vertical and horizontal.

In Marayoor, Areca nut trees are found in plenty and are hence the most preferred wood for construction. Bamboo culms and other small tree trunks can also be used. To further strengthen the mud walls, hay and thatch are added to the mud mixture.

Thatched roof:

Two layers of thatch are laid over each other. The room is then smoked from the inside. The resulting soot is deposited in the bottom layer, which provides additional waterproofing to the roof layers.

This technique is still not completely waterproof. Earlier when tarpaulin sheets were not available the thatch would be up to 5-7 layers thick.

The thatch is made of palm leaves and eucalyptus wood is used to build the roof frame. Above it, a tarpaulin sheet is laid between the thatched leaves to prevent leakage. A second wood frame is then laid over the thatched roof so that it doesn’t fly off in the strong winds.

Comments